DumbDB: Implementing a dumb DBMS from scratch

- 1. DumbDB I: an Append-Only Database

- 2. DumbDB II: introducing the Hash Index

- 3. DumbDB III: from text to results - an high-level overview

Introduction

In the previous post, we implemented an Append-Only Database using CSV files to store the data.

We have seen how inserts, updates and deletes perform really well, being implemented as a single append operation on the table file.

However, queries are not very efficient since scanning the entire table file to retrieve data scales poorly with table size.

In this post, we will see how we can use Hash Indexes to boost the performance of the query operations.

Hash Index

An index is an additional data structure that allows to improve the performance of query operations.

Generally, the idea of indexes is to keep some metadata about the data, so that we can quickly find it at a later time.

Each index worsens write operations, since it implies additional operations to keep it up to date.

However, most workloads have a read-heavy nature, so the performance benefits usually outweigh the additional write operations.

There are many types of indexes, with different implementations, trade-offs and supported operations.

One of the most common type of indexes is the Hash Index - a hash table used to speed up the lookup of a specific value.

For the Append-Only Database, we will use a Hash Index on the primary key column.

The key of the hash table will be the value of the primary key, and the value will be a tuple containing the start byte and the end byte of the row in the table file.

Let’s assume this is our table’s CSV file:

id,name,age

1,John Smith,20

2,Jane Smith,21

3,Jim Smith,22

The hash table will contain:

{

"1": (12, 28),

"2": (28, 44),

"3": (44, 59)

}

When querying for a specific id, instead of scanning the entire table file, we can use the hash table to quickly find the position of the row in the file and only read the corresponding bytes.

Note: A proper DBMS would have a query planner to analyze the query, check the indexes, and choose the best strategy to execute the query.

DumbDB is okay with just assuming the index exists on the primary key and use it for all queries that use the primary key.

Implementation

We will implement an HashIndex class that will be used to store the hash table in memory.

The underlying data structure will be a Python dict of (key, (start_byte, end_byte)) tuples.

@dataclass

class HashIndex:

__index__: dict[str, dict] = field(default_factory=dict)

@property

def n_keys(self) -> int:

return len(self.__index__)

def get_row_offsets(self, key: str) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""

Get the starting and ending offset of the row in the file for a given key.

"""

return self.__index__[key]

def set_row_offsets(self, key: str, start_byte: int, end_byte: int):

"""

Set the starting and ending offset of the row in the file for a given key.

"""

self.__index__[key] = (start_byte, end_byte)

def delete_row_offsets(self, key: str):

"""

Delete a key from the hash index.

"""

del self.__index__[key]

The basic API allows to get, set and delete the row offsets for a given key.

We’ll also implement a from_csv method to build the hash index from a CSV file.

@classmethod

def from_csv(

self,

csv_file_path: Path,

index_column: str = "id"

):

"""

Return an instance of HashIndex built from a CSV file.

The index uses the index_column value as the key and the starting and ending offset of the row in the file as the value.

"""

index = HashIndex()

with open(csv_file_path, 'rb') as f:

# Wrap the binary file with a TextIOWrapper for proper decoding.

f = TextIOWrapper(f, encoding='utf-8', newline='')

# Read the header row and store it.

header_line = f.readline()

headers = next(csv.reader([header_line]))

while True:

# Record starting byte offset from the underlying binary buffer.

start_byte = f.tell()

line = f.readline()

if not line:

break

end_byte = f.tell()

row_values = next(csv.reader([line]))

row_dict = dict(zip(headers, row_values))

if row_dict["__deleted__"] == "True":

index.delete_row_offsets(row_dict[index_column])

else:

index.set_row_offsets(

row_dict[index_column], start_byte, end_byte)

return index

The from_csv method will read the CSV file line by line, and for each line it will add to the hash table the index column as the key and the starting and ending byte offsets as the value.

It also handles deleted rows, by deleting the key from the hash table.

Adding the Hash Index to the Append-Only Database

We will extend the AppendOnlyDBMS class to use the hash index.

To add the hash index to the Append-Only Database, we need to:

- Build the index

- Update the index when data changes in the table (insert, update, delete, compact)

- Query the index when a query is executed by primary key

Note: The index will be kept in-memory and lost when the database is shut down. More on this later.

Build the index

We can build the index when the use_database operation is called, leveraging the HashIndex.from_csv method.

Inevitably, this will be an expensive operation since it needs to read and process the entire database.

@require_exists_database

def use_database(self, db_name: str) -> None:

super().use_database(db_name)

for table in self.show_tables():

self.hash_indexes[table] = HashIndex.from_csv(

self.get_table_file_path(table), "id")

Additionally, we create an empty index when a table is created and delete the index when a table is dropped.

@require_isset_database

@require_not_exists_table

def create_table(self, table_name: str, headers: list[str] = None) -> None:

super().create_table(table_name, headers)

self.hash_indexes[table_name] = HashIndex()

@require_isset_database

@require_exists_table

def drop_table(self, table_name: str) -> None:

super().drop_table(table_name)

del self.hash_indexes[table_name]

Note: Optimizations are possible - e.g. building the index in the background and only using it once it’s ready.

Update the index

A drawback of indexing is the need to keep the index up to date when data changes.

In our case, we need to update the index when a row is inserted, updated, or deleted.

We can leverage most of the logic already implemented in the AppendOnlyDBMS, and only need to implement the logic to update the index.

@require_isset_database

@require_exists_table

def insert(self, table_name: str, row: dict) -> None:

table_file = self.get_table_file_path(table_name)

with open(table_file, 'a', newline='') as f:

csv_writer = csv.writer(f)

start_byte = f.tell()

csv_writer.writerow(list(row.values()) + [False])

end_byte = f.tell()

self.hash_indexes[table_name].set_row_offsets(

row["id"], start_byte, end_byte)

@require_isset_database

@require_exists_table

def update(self, table_name: str, row: dict) -> None:

# This could be omitted

super().update(table_name, row)

@require_isset_database

@require_exists_table

def delete(self, table_name: str, row: dict) -> None:

super().delete(table_name, row)

self.hash_indexes[table_name].delete_row_offsets(row["id"])

We also need to update the index when performing the compact operation. In this case, the most straightforward approach is to throw away the existing index and build a new one from scratch.

@require_isset_database

@require_exists_table

def compact_table(self, table_name: str) -> None:

super().compact_table(table_name)

self.hash_indexes[table_name] = HashIndex.from_csv(

self.get_table_file_path(table_name), "id")

Query the index

Until now, we have seen how to build and maintain the index.

Now we finally see how it gets useful.

As previously mentioned, a proper DBMS would have a query planner to analyze the query, check the indexes and choose the best strategy to execute the query.

Also, indexes could be created also for non-primary key columns, multiple columns, etc.

In our implementation, we always create an index on the primary key column for each table.

For this reason, the query operation will always assume the index exists and use it to execute the query, if the id column is used in the query.

If the id column is not used in the query, the query operation will fall back to the default implementation.

@require_isset_database

@require_exists_table

def query(self, table_name: str, query: dict) -> QueryResult:

"""

If the search is by id, we can use the hash index to find the row.

Otherwise, we need to search the entire table.

"""

if "id" in query:

start_time = time()

start_byte, end_byte = self.hash_indexes[table_name].get_row_offsets(

query["id"])

with open(self.get_table_file_path(table_name), 'rb') as f:

f = TextIOWrapper(f, encoding='utf-8', newline='')

# Read the header row and store it.

header_line = f.readline()

headers = next(csv.reader([header_line]))

f.seek(start_byte)

row = f.read(end_byte - start_byte)

if row:

row_values = row.strip().split(",")

row_dict = dict(zip(headers, row_values))

row_dict.pop("__deleted__")

return QueryResult(time() - start_time, [row_dict])

return super().query(table_name, query)

Benchmarks

Now let’s evaluate whether all this work was worth it.

We’ll run a few benchmarks, both on the classical Append-Only Database and the one with the Hash Index.

The benchmarks will check how the performance of each operation varies, depending on the size of the table.

Note: Absolute values are not meaningful, since the performance of the operations depends on many factors, including the hardware, the operating system, the Python version, etc.

The important thing to look at is the relative performance of the operations.

Append-Only Database

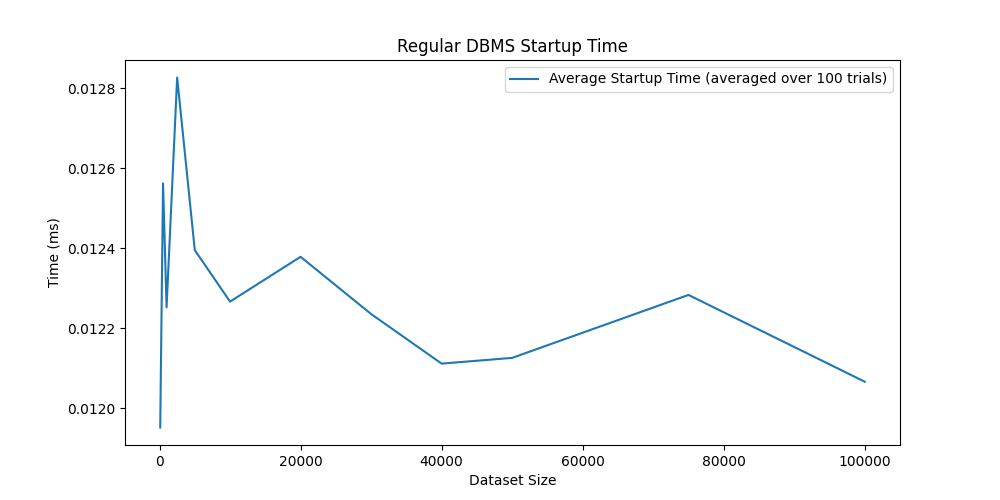

For the Append-Only Database, the startup doesn’t do anything else then checking if the selected database exists. For this reason, the time required doesn’t increase with the table size.

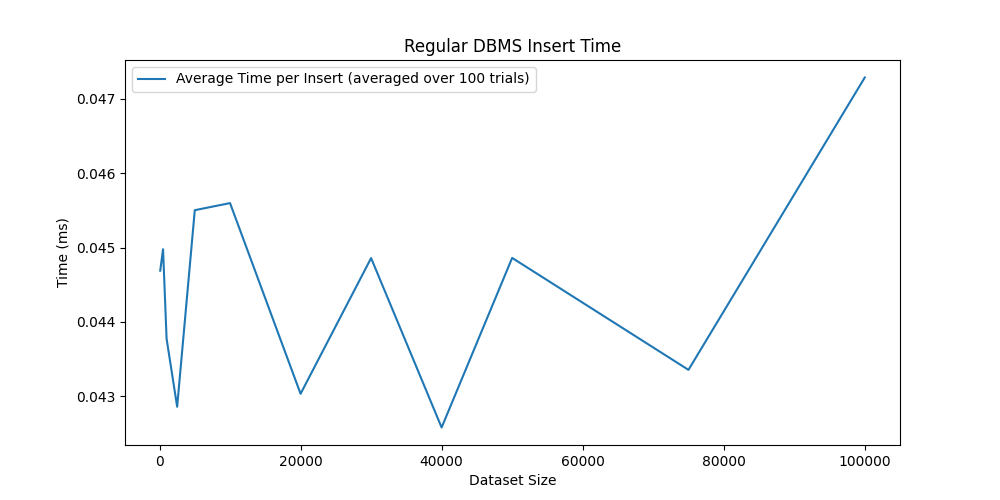

At the same time, inserts are always very fast, since we can use the append operation on the table file.

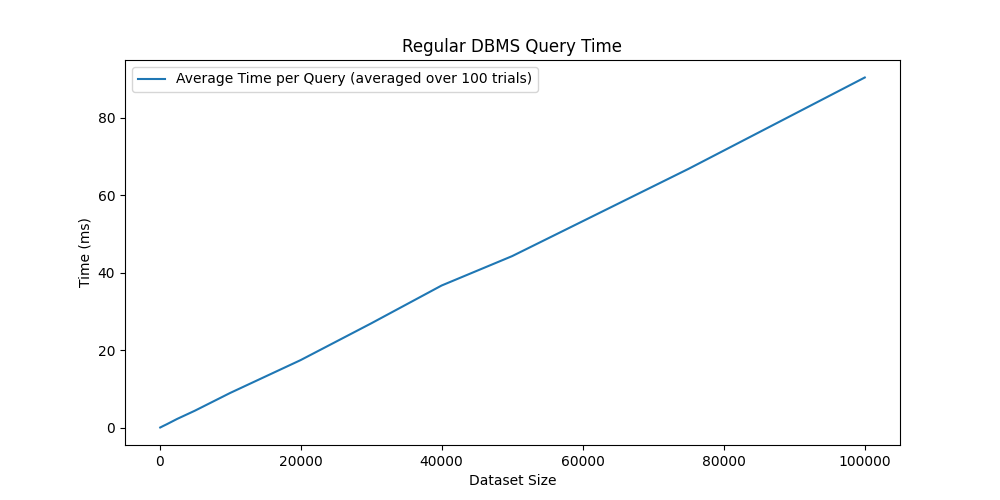

However, the time needed to perform a query grows linearly with the table size, since it needs to scan the entire table file.

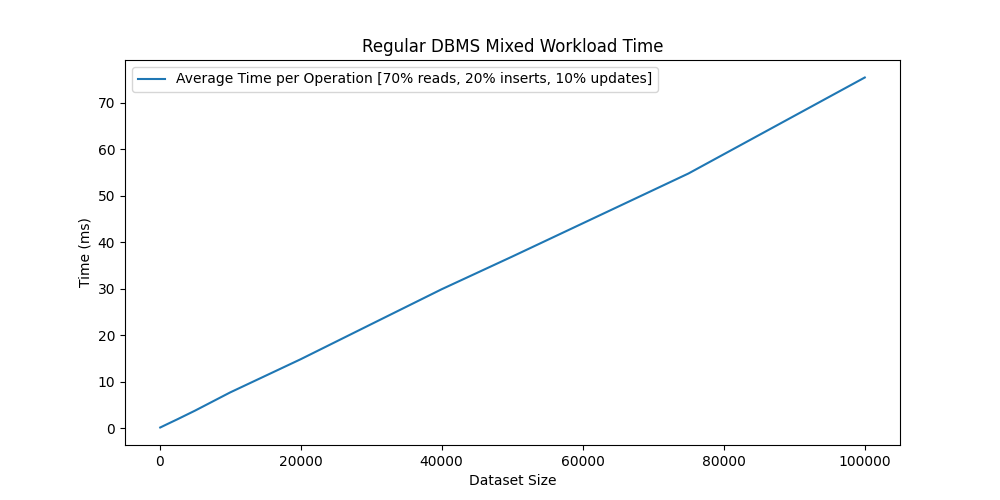

We can also simulate a workload composed of 70% queries, 20% inserts, and 10% updates to see how the database performance evolves.

We see that the query time dominates the total time, so the whole workload time scales linearly with the table size.

Append-Only Database with Hash Index

Now let’s see what happens when we add the Hash Index to the Append-Only Database.

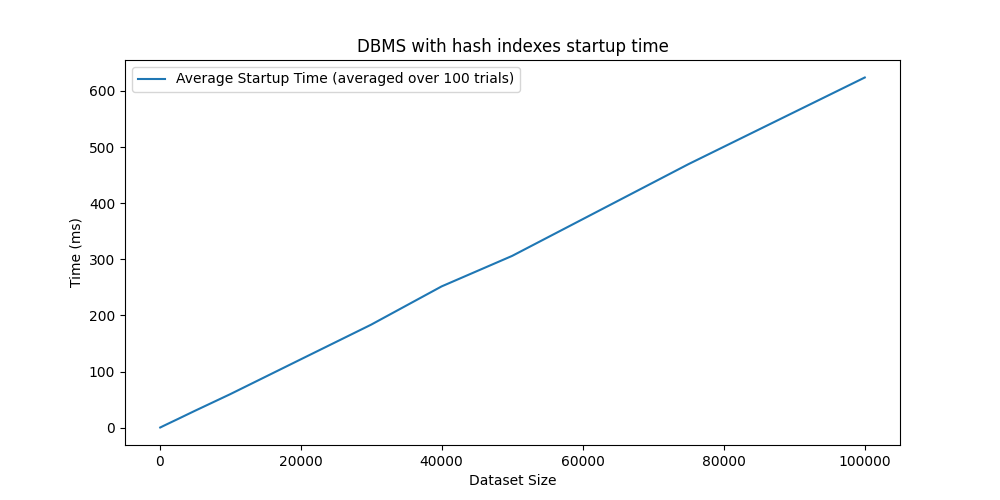

Most of the trade-offs of with indexing involves the startup time, since the index needs to be built from scratch. This operation scales linearly with the table size, and at 100k rows it takes around 600ms on this particular setup.

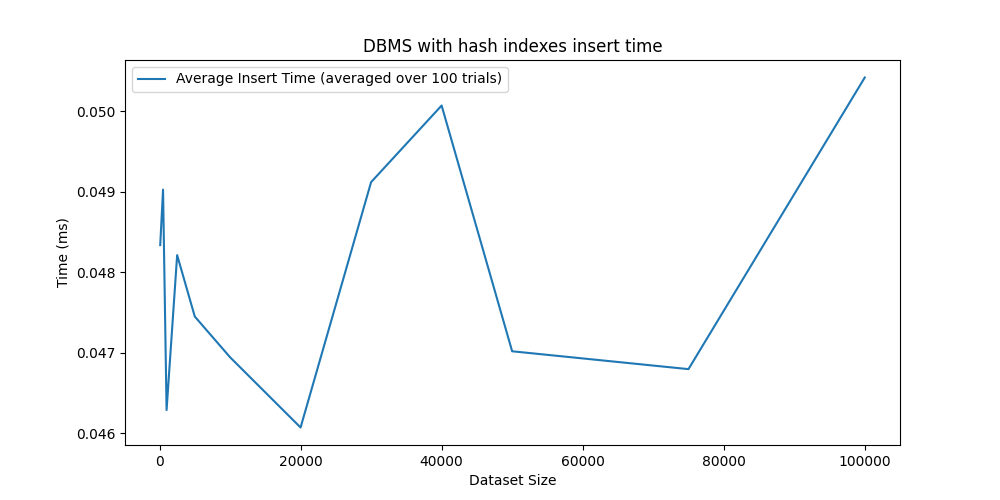

Even if inserts require to update the index, we can see that the performance is practically the same as the regular Append-Only Database.

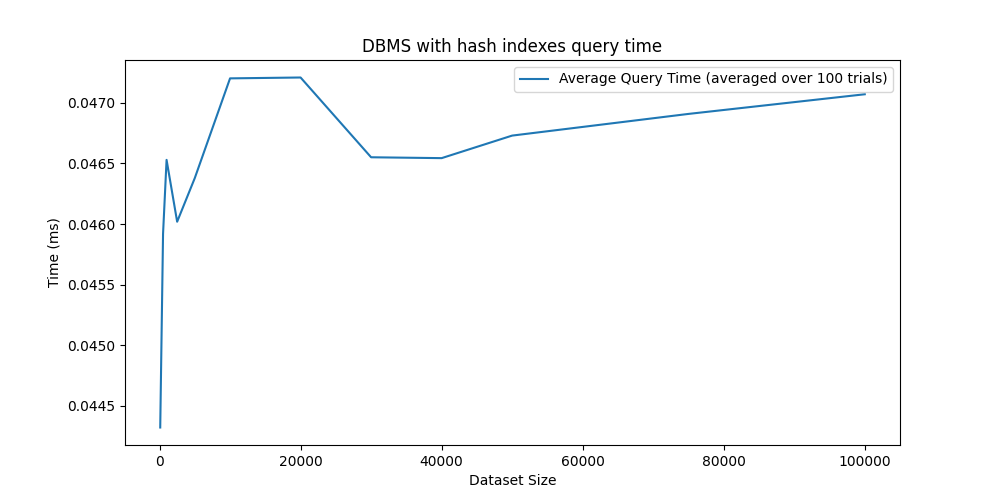

However, we can observe the benefits of using an index for query operations when the primary key is the search key. Queries are now extremely fast—comparable to the performance of inserts. Moreover, the query time no longer increases with table size; a query on a table with 2,000 rows takes the same time as one on a table with 100,000 rows.

With indexes, a query on a table with 100k rows takes around 0.125ms vs 91ms without indexes (a 728x improvement - and growing with the table size).

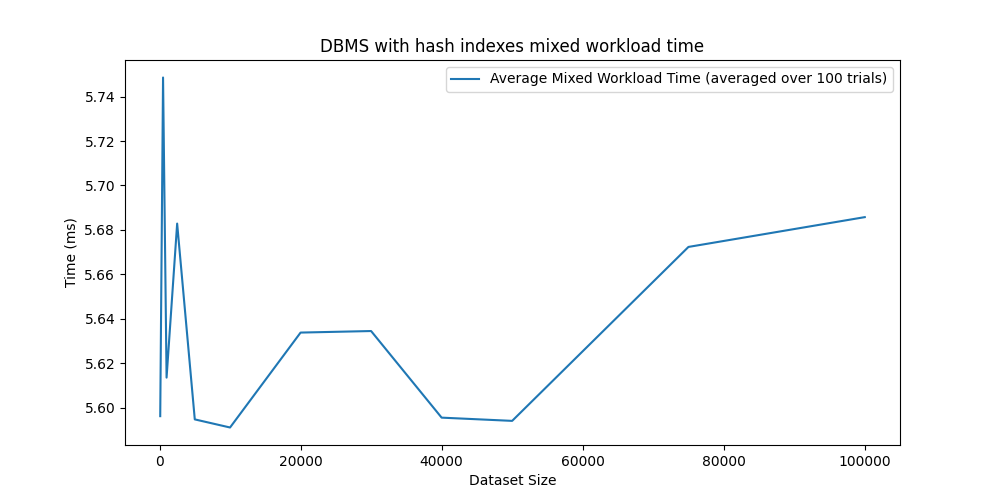

Now also the mixed workload time is constant and orders of magnitude faster than the regular Append-Only Database.

Limitations

Implementing hash indexes as we have done involves some trade-offs.

Memory

The hash index is stored in memory, so it increases memory usage and needs to fit in the available RAM.

However, this is more convenient than keeping the whole table in memory, since the index only contains the primary key values and the corresponding row offsets and thus is much smaller.

Startup time

The most affected operation is booting the database, since the indexes need to be built from scratch. This can be a problem, especially if many tables are present in the database. However there are many strategies to mitigate this issue:

- Use more efficient formats for the data instead of CSV files

- Build the index in background while the database is in use, taking advantage of parallel processing

- Store the index on disk so that it can be loaded into memory when the database starts (this introduces additional complexity and increased I/O)

Queries limitations

The hash index only allows for point queries, where the query specifies a specific value (which are the only type of queries we have implemented on DumbDB).

When other types of queries are needed, such as range queries (e.g. “give me all the rows where the id is between 100 and 200”), the hash index is not useful - other types of indexes are needed.

Moreover, in our simplified implementation, the hash index is only built for the primary key column, and only used for queries on the primary key.

However, with minimal effort, the AppendOnlyDBMSWithHashIndex could be extended to support hash indexes on any column, and use them for the corresponding queries.